Q: What was your inspiration for the story "Am I Like My Daddy?"

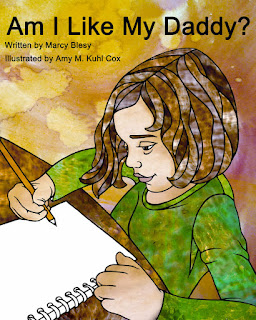

A: AILMD is a picture book in the children's grief genre. Many books in this genre deal with the immediate time after the death of a loved one. In this book, however, Grace is seven. Her dad died when she was five, and she has limited memories. The book is an evolution of her discoveries about her dad as well as herself, how she is unique, and how she is different. The book is hopeful and positive with suggestions for kids going through the death of a parent and how to get the answers they seek.

My dad died when I was 13. I have very few memories. My mom died when I was 24. Very soon after she died I sat down at the computer and wrote all the random things I knew about her because I was so fearful I would forget again. People think that if the kids aren't talking (about the death) then they must be fine (don't upset the apple cart), but in reality, they may not be fine or may have questions they are afraid to ask for fear of upsetting the adults in the family. And, as has been my experience, new questions arise with maturity.

Q: "Am I Like My Daddy?" went through several major revisions. Tell me a little bit about your road to publication.

A: I wrote AILMD four years before publication. Originally the entire story was written in rhyming verse.

I received standard rejections as well as more personal rejections. I received enough encouragement from professionals that I knew I had a unique idea, though. Many of them suggested I rewrite the poem in story form. I also worked at one point with a well-published children's author who suggested I write the story in journal form.

AILMD evolved from poem to third person to journal form to first person to a final version combining first person, journaling, and a small bit of the original poem. I guess you could say I took suggestions and made the story work with what ultimately felt right to me.

Q: How did you find your publisher for such a niche project?

A: I am a volunteer at Lory's Place, a grief education center in St. Joseph, Michigan. The director, Lisa Bartoscek, wrote an endorsement letter for the manuscript that I included in my submission packets.

I submitted 99 times to agents and publishers. Some publishers, including Bronze Man Books, who published AILMD, turned down earlier versions of the manuscript over the years. I was stubborn and persistent.

I submitted 99 times to agents and publishers. Some publishers, including Bronze Man Books, who published AILMD, turned down earlier versions of the manuscript over the years. I was stubborn and persistent.When I submitted the (almost) final version to BMB, a small press university publisher at my alma mater Millikin University in Decatur, IL, they contacted me and asked to meet. Our meeting lead to two more rounds of revisions before they offered me a contract in October, 2011. The book was published in December, 2012

99 "No's"

1 "Yes"

It only takes one!

Q: What was the process from idea to publication? What do you wish you knew then (when you started) that you know now?

A: I had only written a few picture book manuscripts when I first wrote AILMD, so I didn't really know what I was doing. I had always had that dream of being an author, but I was in my late 30s at the time and had to learn the business as well as hone my writing skills along the way.

Oh my gosh, you need thick skin and patience, neither of which I have! But, and I have read this in many interviews with well-published authors: Persistence can trump talent. If you are willing to put in the work and keep learning and improving, eventually there will be a payoff.

Q: Any advice for a first-time writer working with an illustrator? What are some of the most important things in the writer / illustrator collaboration?

A: As is common with a traditional press (even a small one like Bronze Man Books), I did not get to choose my illustrator. You can imagine since this book is in the grief genre that I was nervous an illustrator would be chosen that only saw the theme of the book as sad and missed the bigger picture.

I commend the publisher for choosing such a talented and gifted artist, Amy Kuhl Cox, but I also believe there was some divine work at play, too. :-) Amy brought the book to another level with her beautiful stained glass look pictures. She also focused on the relationship between Grace and her mom who helped answer many of Grace's questions about her dad.

I did learn that the illustrations and the writing are two separate talents, though, and that the finished product cannot exist without each part. I tried to let Amy work her magic separate of my opinions, though I was dying to see everything she did because I was so excited. (This is where my impatience problem gets in the way again.)

The process was very collaborative between the publisher, Amy, and I. We used dropbox to submit the manuscript changes, early illustrations, etc. so we could all respond. I had asked Amy if I could send her a picture of my dad who died when I was young. I didn't know if she already had an idea for a dad or not, but "just in case." She agreed. When I opened an early file version of the pictures you could imagine my surprise when I saw a drawing that was later inserted into a picture frame in the background that featured a drawing the family picture of my dad, mom, and I that I had earlier given her. What a nice gift she gave me.

Q: A specialty publication has a specialty audience. How do you go about finding ways to connect your target readers with your book?

A: Local events don't work well (except for my personal book launch) because people don't go to book fairs to buy a book in the grief genre. However, online marketing works. The publisher and I targeted grief organizations, counselors, etc. Compassionbooks.com is a leading grief resource website. They are very selective in the materials they sell on their site, so I was thrilled that AILMD was selected as one of only 12 books in the "loss of a parent" category. Amazon has continually sold out and reordered copies of the book.

The publisher generously offers the book for sale at wholesale price to organizations that purchase ten or more copies. They can then sell the copies, if they choose, at full price ($12) and use the money for fundraising purposes. For example, I run an elementary library. We knew a lot of students would buy the book simply because of the Mrs. Blesy connection. From the 60 books that were sold there, $360 went to Lory's Place. This is an offering the publisher makes available to anyone.

I also blog occasionally about children's grief. AILMD has its own facebook page, and I use twitter to connect with other grief organizations.

Q: In addition to traditional publishing, you have also had some success in self-publishing your YA stories. Tell me a little about the Lexie and Rhett Chronicles. What factors made you decide to self-publish?

A: And yet again, that impatience creeps in! The traditional publication route takes a long time with no guarantees (at least for me). As an experiment of sorts I decided to dip my toe into the e-publishing world using Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing.

I have written a middle grade and young adult novel, so I wrote a YA short story called "Prom for One," about a disasterous prom night that has a sweet twist for its main character. The story is 10,000 words.

I priced it low because of its word length and hired a photographer friend to take a picture of another friend's prom dress for the cover. Formatting was a nightmare that I have now mastered, though. I had a couple of beta readers offer their opinions, too. Then I clicked "Save and Publish." Fast and inexpensive!

I hit social media hard with marketing. I have sold 375 "Prom for One" copies since March and published the second and third short stories in The Lexie and Rhett Chronicles ("Graduation for Two," "Test for Three"). In addition to the individual sale of the three stories on Amazon at .99 apiece, I also sell the virtual "box set" of the trilogy for $2.99. The second and third stories are selling themselves as I have the links at the end of each story to the next one in the series. I also buy premade covers now from a great website.

I have been very pleased with the responses I have been receiving and the immediacy of it all. Although, let's be honest, at .99 a story I am not making big money here.

However, I love the creative outlet and continue to write. You never know. In addition, I continue to query agents and traditional publishers with two more picture book manuscripts.

Q: In your experience, what are both pros and cons of Traditional vs. Self-Publishing?

A: Traditional: Pros's:

* That sense of accomplishment in that others in the field justify that what you are doing is good enough to invest money in to publish.

* Professionals who take care of the business details of publishing.

* Payment can be nice.

Self-Publishing: Pro's:

* Control belongs to the author (which can be seen as a pro or con!).

* Speed of publication.

* Ability to get feedback from readers more quickly.

There is still a bit of a stigma with self-publishing, but I really think e-publishing has shaken things up in a good way. I love it, but I would love to be published by a big NYC publisher, too!

Q: I love the story about what you learned from a "bad" review and the valuable lesson you learned from it. Would you share?

A: Most of the feedback for "Prom for One" and "Graduation for Two" has been positive. I did have a funny, though not-so-funny at the time, experience with my latest and final story in the trilogy, "Test for Three." A reviewer left a horrible, one star review, not for plot, characters, grammar, etc. (any of the things warranting a one star), but because I didn't have a "happily ever after" ending. The first two stories definitely do.

Apparently, since I have been marketing the series as a romance because it is a great love story, diehard romance fans expect a particular prescription to their books. I now don't use the word romance since the third story doesn't end with the characters walking into the sunset (insert sarcasm).

Truthfully, it was a painful lesson, but with self-publishing there is a lot to the business of publishing you have to learn on your own. I am still quite proud of the ending and would never change it to meet the "romance" requirement. When I read that others have cried or that the story stays with them, that makes me feel good. Those are the responses I wanted when I wrote it.

Q: What advice would you give to someone considering self-publishing short stories?

A: If you don't want to invest in the time for a full length novel or you are just really good at writing short stories, I say go for it! The feedback is helpful and fun. Just be clear in your title that the story is a short story (list word count in the description) or reviewers expecting a full length novel may feel cheated and review you in such a way.

Q: In your experience, what aspect of publishing surprised you the most? What did you learn from the experience?

A: Things change! In the last five years, most publishers no longer want paper submissions. Queries happen over email.

You can put so much work in the submission process or after publication marketing process that you forget to actually write! I know I have been guilty of this. Don't stop writing.

Everything I write gets better and stronger. I don't make the same mistakes as I did in earlier manuscripts. I know that later manuscripts won't have the same mistakes that current ones might have. If writing is your passion, then follow it. You won't have regrets.